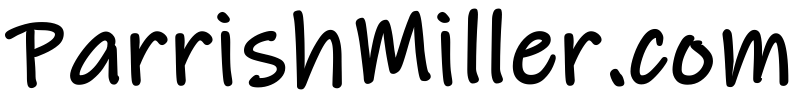

Even among those who subscribe to the non-aggression principle (NAP), there are some who do not understand the nature of obligations, responsibility, and the inalienability of the will. While a thorough discussion of these issues could fill many volumes, it is my desire to provide a simple summary for those who desire an overview of the subject.

First things first. The framework required for understanding these arguments and positions is that the NAP is an objective moral fact. It is always wrong to initiate force against another individual. If you disagree with that, so be it, but don’t bother trying to argue against the rest of this article if you’re not even going to accept the basic premise.

The second basic premise here is that the NAP creates certain negative moral obligations that require refraining from actions that constitute the initiation of force against others, but it creates no positive moral obligations to engage in action. This is not to say that there are no personal preferences or personal moral codes which may require action or by which one may impose obligations upon themselves, but these are, in fact, preferences, and not objective truths. Personal preferences do not create objective or universal constants.

In order for the NAP to be followed, all actions must be entirely voluntary; that is to say, they require affirmative voluntary consent and that voluntary consent must be ongoing. The individual is always free to withdraw consent. This principle is known as the inalienability of the will. The individual’s will (in essence, the ability to change one’s mind or to grant and withdraw consent) cannot be surrendered or alienated. For something to be inalienable means that it is “unable to be taken away from or given away by the possessor.” In other words, even if you wanted to give up control over your will, you can’t. It is inseparable from your existence.

The only caveat to the inalienability of the will and the withdrawal of previous consent is that the individual must restore to their previous condition or to a similar position, anyone over whose life or safety he took charge when his consent was in force. This applies equally to a child taken into the woods by his parent, to an airline passenger of the pilot who decides he no longer wishes to be a pilot halfway through a flight, and to the patient on the operating table whose brain is exposed before the suddenly retiring neurosurgeon.

The parent is not obligated to raise the child to adulthood, the pilot is not obligated to fly his customers across the globe, and the neurosurgeon is not obligated to perform brain surgery, but each does have the obligation to restore their charges to some degree.

The parent must return the child to civilization where his care can be assumed by another. The pilot must at least land the plane rather than simply donning a parachute and abandoning the plane at 30,000 feet. The surgeon must at least stabilize and close rather than leaving his patient to die on the table. Alternatively, in each of these situations, the individual could simply turn the responsibility over to a second willing and capable parent, copilot, or surgeon and be free to exit immediately.

In all of this, the central goal is respecting the autonomy and self-ownership of the individual by recognizing that no one can assert a claim on that individual which supersedes his own will. At the same time, we must recognize that the relinquishment of a previously voluntarily accepted responsibility may require some minimal obligation to restore individuals whose well-being has been put at risk.

You might well object that the previous paragraph is at odds with my earlier assertion that the NAP “creates no positive moral obligations to engage in action,” but the difference is that we are now dealing with responsibilities which were previously accepted voluntarily. Put another way, there was no obligation to take a child into the woods, pilot a plane, or perform surgery, but, once begun, these actions require completion or at least restoration of the individuals involved.

To do otherwise would be to engage in an action that constitutes the initiation of force against others, and such actions are prohibited by the negative moral obligations created by the NAP. To abandon a child in the woods, an airline passenger at 30,000 feet, or a patient on the operating table—when you are the one responsible for their presence there—is not merely a refusal to act, it is an action designed to harm.

This apparent dichotomy can be likened to the restoration owed to the victim of a crime. If you punch someone in the face, you owe them a debt of restitution. You had no obligation to them until you chose to punch them. Likewise, you have no obligation to anyone unless you choose to take it on, and you can most certainly divest yourself of it, but to do so, you must restore the person to their state of relative safety which existed before you accepted the responsibility.

In summary, it is always your choice to take on a responsibility, but once you do, you can only extricate yourself from it in a manner that does not constitute the initiation of force against others. This voluntarily accepted responsibility is not a positive obligation, but not causing harm to others is a negative obligation. If you don’t want to risk being caught in such a scenario, do not accept responsibility for another person’s safety or well-being. If you do take on such a responsivity, do not abandon it in a manner that causes harm to others.

All of this is actually rather obvious and self-evident, in my opinion. A little common sense goes a long way.